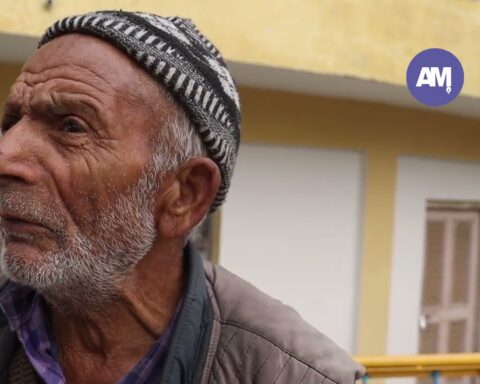

Kashmir: Sitting inside his small handloom unit on the outskirts of Kashmir’s Pulwama district, a wiry Mohd Akbar Sheikh(68) is waiting for some work.

The handloom sector has been hit hard since the power loom industry had a major boom. The greed for profits, and with supplies of hand-spun yarn and hand woven shawls falling short of the growing demand, it has led to a proliferation of power looms in Kashmir, threatening the handloom tradition. It’s a similar saddening story for the carpet industry as well.

The roots of handloom Industry in India can be traced back before the freedom struggle of India as Mahatma Gandhi favoured handlooms, and expounded his views way back in 1919. But in Kashmir valley it is the legacy of the Mughals that it evolved over three hundred years under the patronage of four different rules. Some of the craftsmen in Srinagar have managed to revive that old glory and provide replicas of 16th & 17th century hand embroidered shawls. It even takes 5-12 months to prepare a hand embroidered shawl.

Pashmina embroidered shawl is one of the most successful items in the handloom sector of Jammu & Kashmir. Unbelievably soft, made even more beautiful by intricate hand embroidery, the shawls, made from the fleece of the pashmina goats, are primarily associated with luxury and wealth. Visitors to this beautiful Valley should not consider their trip fruitful until they’ve had a chance to experience the pashmina so symbolic of the warmth in the hearts of the people.

“It was started by Gandhi and I love this profession as it was the only means to mitigate the rural poverty, but now the government shows a tendency of failure to protect us” said Sheikh.

He further said that before few about 10 years back, the whole area of approximately 20 villages were involved in this handicraft as it was second largest source of income after agriculture but now people shifted dramatically to other businesses as government overlooked after it.

Expressing his loose sleep he said that, in earlier, government used to supply a plenty of raw material (yarn) and work through Ghandhi Ashram, Khadi commission and Dastkaar Handloom corporation as we were manufacturing 1500-2000 meters of cloth per month but now a days we can not produce even 1500 meters throughout a whole year.

“The only reason which is not allowing me to leave the profession is my age as I can not start my another business in this age now, it’s my ancestral job even we have now remained just two units in the whole area” he said.

While talking to another weaver Arsheed Ahamd sheikh(38), he said that, I am into this buisness since past 20 years, it was running smoothly when I started but now we are suffering from some inherent problems like low productivity, lack of product diversification and problems related to procuring raw materials. The co-operative sectors are indifferent to enlarging their market sphere.

Giving a detailed reason behind the setback of this industry he said that the government institutes which provide us raw material started sending us low quality yarn and at the same time private handloom corporations use high superior quality of yarn and they have also upgraded handlooms to power looms, because of the quality products our products resulted in bush-off by the people.

“The new generations are totally unwilling to accept weaving as their occupation because of the uncertainty of the industry.” He said

He further added that a decade before, a clusters of villages in almost every district from south to north of the valley were associated with loom but you will hardly found few these days.

Abdul Rehman (75) greybeard weaver put across the same version that the art is about to die as it seems desperate that being in this profession is worthy now. My grandchildren don’t even think to carry on this profession as they hardly see me earning a few bucks from it.

“I started hand looming before 65 years and I have taught a lot of people in these years, people were enthusiastic to learn at that time because they used to earn a good amount from it but nowadays nobody comes to learn it, not even my own children, it’s because traditional weavers don’t earn from it now they prefer other businesses over it, I am feeling down in the dumps by watching this art dying, as it’s declining day by day” Said Rehman.

Farooq Ahamd Mir a quinquagenarian man lives in Inder village of South Kashmir; in kashmiri language Inder means the Charkha(Spinning wheel), he says my family is in this profession since 90 years.

“One piece of original Pashmina Kani shawl ranges from one lakh to 5 lakh, people now don’t prefer to buy such costly cloth even in international markets because of inferiority mixture in the raw material” said Mir.

He further said that government have established a Handloom Development Department to look after handloom but they don’t pay much attention toward us now. We are compelled to work individually on our own as we buy raw material from local dealers then sell it to brokers.

“My children don’t want to continue this profession as they saw me in slumping situation, I am afraid to watch my ancestral profession dying” he said.

Meanwhile the director of Handicrafts & Handloom Kashmir, Mehmood Ahmad Shah said, the methods and attempts to enhance the sector to an elevation are being prioritized through serious approaches. “The department has been merged into handicrafts and handloom. Both of them were initially segregated at first but now we have one department looking after both of them because we don’t differentiate between them”. He further informs, “All the schemes which have been initiated in the last two years have laid emphasis equally on both of them. We have financial assistance to look after the societies where we aggregate provide the artisans with the required assistance”

While questioning on the reduced demand of handloom by the introduction of power looms he agrees on introduction of power looms has led to the marginalization of handloom workers. “To ensure that the pieces made on handlooms are given the deserved importance through GI tags for markets helps to recognize and sell the handmade pieces. That explains that the ones apart from the GI tag are made on power looms. For this, we are focusing on the advertisement and promotion of GI at airports, hoarding, Instagram, Twitter, and other social media platforms. The aim is to explain why people should purchase handmade instead of machine-made”.